Kyle Steed: The War of Art

The idea for this interview came about when my friend Josh Read mentioned that Kyle had been in the military. That seemed strange to me. Kyle didn’t seem like a guy who’d been in the military. But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Kyle is disciplined, put together, responsible. He recently became a father. But at the same time, he wears hats that may or may not have feathers in them. His quirkiness just didn’t jibe with my idea of a soldier. So I asked Kyle if he’d mind grabbing a beer and setting me straight. As you’ll see, we got spectacularly off topic.

Here’s my chat with the one and only Kyle Steed.

The Kyle Steed, circa 2012.

I can’t remember how it came up, but I heard you were in the Army.

Air Force, yeah.

So we were like, “Oh, maybe that’s why he’s so disciplined.”

Well, you know, Elvis was in the Army.

Was he an artist before he went in?

Probably. I mean, I would say the same about myself, too.

Were you pretty young when you first started creating stuff?

Oh, man. We would have to call my mom.

Let’s get her on the phone.

Haha, now might not be a good time for her. Can I get a bottle of water real quick?

Sure, one sec.

[Water break. Someone is playing James Blake over the stereo: “Limit to Your Love.”]

Let me put my phone on do not disturb me mode. Take two.

Take two. So you were pretty young when you first started creating things.

I don’t know if I could clearly pinpoint an exact day that I picked up a pencil and thought this is what I want to do with my life. For me, it was always just a form to express myself. Maybe it was easier than words for me. I believe God made me to be a visual person.

Were you a good student?

I was an okay student. I wasn’t a great student. I was bored a lot of times, so I would just sit and draw on my notebooks and not pay attention. I had this weird fascination with drawing house plans. I would sit down with graph paper and from memory draw out the house plans of the house that we lived in. Then I would go off on tangents and make these elaborate mansions with full basketball courts and swimming pools and indoor soccer fields. I would show them to my parents, and my parents would say, “Oh, these are nice.” My mom still has some of the stuff framed in her house now. Maybe that’s what helped encourage me. We always look to our parents for affirmation.

Yeah, it’s huge.

I was very fortunate, I think, to have been born at that time. Now I don’t think children are given enough room to be bored. Their schedules are full with sports and extracurricular activities at school, or they’re on their phones playing games. I’m a big believer that if you don’t have downtime to be bored and to figure out what to do with your boredom, you don’t grow creatively.

Kyle in Art Class, 1999.

Can you remember a point when you decided to start taking your art seriously?

I can remember my freshman year of high school, in art class, really finding my niche in drawing and collage work. High school was so awkward though. I moved to Nashville my sophomore year to be with my dad. I changed high schools, changed friends. I got in with the Goths, like the skater/punk people. I got heavily involved in skateboarding. That became my life.

You were a skateboarder?

All through high school. Every afternoon after I got home, we would go skate. I think the best thing I ever did was Ollie down seven stairs. It was so intimidating. You roll up to it, measure yourself by it. But I landed it. Skateboarding is a total mental game.

Really?

It’s 90% mental, 10% physical.

What do you mean? I need help. I can barely stand up on the board my wife got me for Christmas.

You have to believe you can do it. You have to overcome the mental obstacle of imagining yourself doing stuff before you’ll ever physically do it. Because if you psych yourself out, then you’ll either really hurt yourself, or you’ll just never try it.

Photo by: Matt Pittman, friend and co-founder of Folly.

Were you starting to take design more seriously in high school? Or were you too busy skateboarding?

Around my senior year I took a design communication class, and it was the first time I ever saw an Apple computer. What was it? Maybe it was a G3 Power PC. It was blue and had a 17-inch flat display. It had Photoshop on it, Photoshop 5.0. I think this was before OS X was even out.

Our assignment that year was to create artwork manually and then scan it into the computer and create the final piece using Photoshop. I created this cheesy little album cover for a hip-hop mix tape. I drew this DJ and then I scanned him in. It was really bad but I worked hard on it.

After I graduated high school, the only thing I wanted to do was go straight to the Art Institute, but it didn’t end up working out. It was too expensive. So I moved to Texas in October of 2000, and I started going to community college in Fort Worth. I got an internship that summer, which was a high point. I think it was the summer of 2001. The internship was for an in-house design team in a pharmaceutical company. It was so random. I did it for the summer from May or June until August.

Kyle (right) standing with his brother at his high school graduation, 2000.

So you showed them some samples or something?

I just had my same high school art portfolio that had pastel drawings and paintings and stuff. I laid it all out in their boardroom, on their big, long conference table. For some reason or another, they decided to hire me just based off the work samples I showed them. I had no work experience.

By Kyle: 2003

How old were you? Like 20-something?

I was 19. My art director was awesome. She was super old-school, all print. She taught me about ordering paper samples and talking to paper reps. Just the process of taking a design from conception all the way through to the end. She was really good at feedback. I remember she sat on one end of this extended cubical, and I had this little tiny desk on the other end.

It’s funny now, looking back on it, because I did a lot of icon design at the time. These were like the worst icon designs I ever made. I think I’ve still got them saved on a CD-ROM somewhere. They were all created in Illustrator. They might have just made something up for me to do for all I know. But I think things like that are important to keep you humble. You can look back at your earliest work and be like, “Oh, my gosh. I made that?”

Anyway, the internship ended that summer, and the next semester I stopped going to community college. I failed one of my classes, and my parents were like, “Okay, we’re not going to continue paying for this if you don’t show the effort or really care.” So I was like, “Fine, whatever. I don’t like school anyway.” So I started working customer service jobs, dead-end places.

So you just went out and got a job.

Yeah, I worked at Central Market for six months. I worked at a golf course cleaning golf carts. I worked at Mailboxes, Etc. shipping packages and making copies. The most embarrassing one is I worked at an ice cream store for a week before I went into the Air Force.

So, okay — this is what I wanted to ask you in the first place — why the Air Force?

Well, my dad had given me an ultimatum. He was like, “Either you get a job and start paying your way around here, or you can just go into the military and they’ll teach you how to take care of yourself.”

The Steed Family, 1984.

I was so spoiled at the time. I didn’t understand the value of working hard and earning something. So I ended up in the Air Force. I’ll never forget the first night being there, going to sleep in that bunk bed. I had to sleep on a top bunk. It was probably a foot too short for me, so my feet hung off the end. And the thing about the military is that there’s no style. It’s completely stripped of anything that would resemble taste. You sleep in a big dorm room with 50 other dudes. The first night they were yelling at us, “You have five minutes to strip down, get in the shower, and then go to bed!” I’m like, I’ve never been naked around 50 other dudes before, but it’s not like you really have a choice. Everybody is lined up in the shower room. It’s just like herding cattle.

That sounds like a nightmare.

I just never experienced anything like that before. It was just a shock of reality.

In retrospect, though, basic training was one of my favorite times in my life, just because they strip you down. You don’t have a cell phone. You don’t have music. You don’t have anything. I took a Bible and some clothes. Anything beyond that, they provided. I was reading my Bible and praying a lot. It just felt like a really good connection there, spiritually. Which is kind of weird because the next year was a total night-and-day difference. Once you got out of basic, they gave you all your things back. I could have a cell phone, and I could listen to my own music. It’s like I had all these options now, but I felt more spiritually dry than when I’d been stripped of everything.

It’s kind of like you were saying about boredom. Having options can end up being a bad thing.

It hinders us. Because what do we do? We fill our time with what feels good in the moment, what’s visually pleasing to us. It turns our brains off.

Were you doing anything creative while you were in the Air Force?

I started journaling a lot. I’d been journaling for a long time actually. This was all happening under the surface, paving the way for what I’m doing today. I can remember, before the military, sitting in my room, looking at one of my journals, and thinking, This is what I want to do. I don’t know how, but I want to take what I’m doing here, these words and pictures, and I want to make a living from it.

By: Kyle, 2006.

That was a pretty clear thought you had?

It was very distinct. I remember talking with my girlfriend about it. So I carried my journaling with me through the military. I would doodle and draw. It was therapeutic. I didn’t really have anybody I could confide in. I didn’t have any really good friends. Journaling was a compulsion. It was just a natural part of my rhythm at that time.

Did you know that when you came back you were going to give art a try?

Well, I ended up getting married and getting transferred to Japan. When it came time to actually go back home, I didn’t know what [Amanda and I] were going to do. We didn’t have a car. We didn’t have a house. We didn’t have jobs. But I knew the Lord was saying, “You’re done. You can go back home.” I remember there were nights when I would lay there in bed and just really trust in the Word. Matthew 6, the part where he’s talking about the birds in the air and how much he cares for them. He’s telling us not to worry.

Were you worried?

I mean, about as worried as a person can be who is completely relocating their new family and just starting over again.

So what happened?

Well, one of my wife’s good friends and her husband had a house, and they let us stay with them for two weeks. When it came time for me to find a job, I went to Walgreens up the street and I was like, “Hey, do you all have any job openings in your photo department?” So that’s where I worked.

Walgreens?

My first job after the Air Force was at Walgreens.

Developing people’s photos?

I didn’t even get to develop them. I was an assistant. I got to watch somebody else develop them. I think I worked there for two weeks before getting a job at Half Price Books. I worked at Half Price Books for a month. I distinctly remember lining up the history books one night after we’d closed and thinking to myself, I can’t stay here. This can’t be my life. I can’t go back to doing what I did before the military.

It’s funny, I just went to Walgreens a few days ago to buy my daughter some baby Tylenol, and there’s a lady still working there from when I was there. People just…stay.

So you decided you needed to be designing? You couldn’t be lining up books anymore?

Yeah. This is another testimony of how awesome God is and just his sense of humor. One of Amanda’s good friends had started working in web design a few years before. She knew I was interested in graphic design, so she told me, “You should really think about doing website stuff. There’s good money in it.” So she basically held my hand and walked me through some very basic, low-level HTML stuff. She taught me how she did things. She helped me create a résumé and put me in touch with this headhunter lady.

One afternoon at Half Price, I was on break, and I got a call from this lady. She was like, “Hey, there’s a company really close to where you guys live, and they’re looking for a web designer.” I was like, “Heck, yeah!”

By: Kyle, 2006.

That first job, they started me out at $35,000 a year. I was like, “What?! Big time!”

By October I was in that job and I was so over my head. I knew next to nothing. I started going to night school, thank God, because my teacher was awesome. She taught us all about how to make tableless CSS design. I was going to class at night and coming into work the next day and applying it.

Were you screwing up a lot of stuff?

I felt so overwhelmed. I would come home from work stressed. I was like, “They’re going to fire me. They’re going to find out that I don’t know anything, and it’s going to be over.” I had a great manager though. She was awesome. She actually just brought us some food after my daughter was born.

How long were you at that place?

Two and a half years. That’s really where I cut my teeth. I never encourage anybody to go work for themselves right out of college. That’s the last thing I would tell somebody to do.

Really?

Yeah, because if you get thrown out there on your own, it’s going to take you 10 times longer to learn than if you’re at an agency. At an agency, you’re going to learn how to take critique, you’re going to learn how to accept feedback on your work, you’re going to learn how to put the client’s needs ahead of your own.

Do you want to get a beer now?

That would be awesome.

[Beer break. Beer choice: Velvet Hammer]

Oh, wow, that’s amazing.

Yeah, and it has super-high alcohol content too. Like nine percent. So, when you finally started working for yourself, did you feel like, “Okay, this is what I’ve been working for since I started doodling back in high school?”

It felt like a coming to fruition. I felt like I’d been transitioning into it over the years while I worked for Wave Two, that first agency, and then Fellowship Tech. I was always doing side projects and freelance work. I remember at Fellowship we had a hack day where each person could work on a personal project, and that’s when I made my first font. I made it in less than a week, I think.

Do you feel more invested in your work now that you work for yourself?

I feel like anytime somebody’s paying you to do something, you should give it your all. But there is something really great about giving the client more than what they asked for, something that leaves a lasting impression on them. It’s kind of like a fun little game to play. How can I do something extra for these guys that they’re not going to expect but they’re totally going to love? It’s unique to each project. There are a lot of people who just meet the minimum because they don’t love what they’re doing.

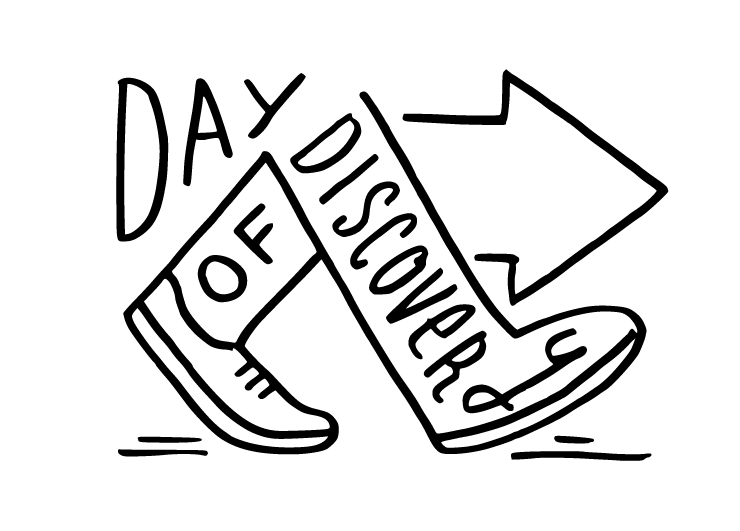

Kyle's hand-drawn words on the wall of Union Bear restaurant in Dallas

Kyle's hand-drawn words on the storefront of Milk & Honey boutique in Dallas.

So I’ve been wanting to ask you this for a while: How hard do you try?

How hard do I try?

Yeah. Like, how much effort are you putting in? How much effort does it take to be a successful artist?

You know, I think the moment I stopped trying to be perfect in the work I did, a whole new door opened.

When you stopped trying to be perfect?

Yeah, when I started embracing the imperfections.

So you stopped trying super hard.

Yeah, and that seemed to be so much more freeing. I was able to be like, “Well, that doesn’t look perfect, but that’s what I did. Do you like it?” Sometimes I feel like I try pretty damn hard to either get clients or to drum up new work. Even today I was thinking, Am I charging too much? Is it just not the right fit? What’s happening? But there’s such a fine line between hard work and striving, and they’re two totally different things.

Which one’s the bad one?

Striving is the bad one. I feel like if I’m always striving in my work and trying to get clients, trying to make a name for myself, trying to be known on Twitter and Instagram — I’m doing all of these things for my own, and there’s no room for God to have any glory in it. God calls us into a place of rest. And by walking with him, we can still do hard work because there’s value in working hard. But it allows some wiggle room for God to show up and for him to do things that we didn’t think were possible.

I haven’t posted to Instagram in two or three weeks. Somebody might look at that from the outside and be like, “You’re crazy. Why would you not continue to post images every day to build your following?” I’m like, “Well, what’s the point?” Not to say I’m not thankful for everything, but I don’t want to strive. I think Thom Yorke said it best on The Bends: "You kill yourself for recognition."

I think what’s helped me, too, is not comparing my work to other people’s work. That’s so harmful. If I’m working on something and I’ve got some other people’s work on the screen, I’m like, “Mine doesn’t look as good as theirs. Mine is crap.” I’m robbing myself of the joy I can take in my work — the joy of being happy with what it is.

You don’t care how you stack up?

It's not that I don't care how I stack up anymore, but that I don't let that affect the way I view myself and my work. Obviously the world and the internet are going to stack me up according to numbers of likes and other superfluous statistics on the work I post. But at the end of the day, I am not defined by my work alone. Comparison is very easy, and it’s very subtly driven into our culture. I think there’s a healthy way to do it, but I don’t know what it is.

I guess there’s a way I can look at someone’s work and say, “Man, that’s great. That really inspires me,” but I’m not going to look at your work and try to copy it. If we’re just trying to meet somebody else’s standards, we’re never going to be ourselves.

Looking at where you’re at now — a professional doodler like you’d hoped to be back in high school — would you have any advice for that younger version of yourself? Anything you wish you’d known earlier?

I wish I knew how to try things and not be afraid. I wish I knew I could actually start doing something back then and not just sit on my hands waiting around. Maybe that’s why it’s taken this long — 10 years. I had to overcome that sense of entitlement. That’s what I would have told myself, but I know I wouldn’t have listened. I had to experience it on my own.

It’s so surprising how much time it actually takes to build a career. Ten years. That’s a long time.

That’s the biggest thing I could ever hope to get across. You can’t expect everything to happen right this second. You have to be patient, and you have to put in the effort. Hopefully you can work your whole life and get better and better at what you’re doing. If you’ve found what you love to do, it should take your whole life to master it.